I’ve spent the last year researching the trust and safety mechanisms in SCM platforms like GitHub, GitLab, and Gitea. These platforms are important in the ecosystem, as GitHub and GitLab together host most of the world’s source code. My interest in their trust and safety mechanisms was driven by my experience as a red-teamer and software supply chain offensive security practitioner.

For years I’ve used GitHub and GitLab components in my red-team engagements. For example, the file upload service which I’ll talk about today is a great way to host attack chain components when you are targeting software engineers. I mean, what better domain is there to use than “github.com”, right? Red teaming is all about emulating attackers and the reality is that GitHub is where bad guys are hosting many of their attack chain components, so why not do the same?

Bad guys make fake GitHub and GitLab accounts which I call “Code Puppets”. Bad guys also use malicious NPM packages and GitHub repos to pull their payloads from. Supply chain threats are made worse by the sheer number of ways that threat actors can use to poison your applications. I teach these concepts in my “Red Teaming the Software Supply Chain” training.

My trust and safety research finds new attack vector in GitHub and GitLab

I’ve identified a brand new type of attack that I’m calling “repo swatting”. This attack targets developers’ accounts on major source code management (SCM) platforms like GitHub, GitLab, and Gitea. This malicious technique allows attackers to potentially delete a user’s entire account or repository, posing a significant threat to developers and their intellectual property.

So, what exactly is repo swatting? I coined the term as a nod to the infamous “swatting” practice where bad actors make false emergency calls to provoke an armed response at someone’s address.

Repo swatting is similar to real swatting in the sense that the attack abuses the trust and safety mechanisms in the SCM providers to do harm instead of good.

tl;dr

This attack is straightforward and abuses the trust and safety processes in the SCM platforms to delete the target accounts:

- An attacker exploits a “feature” in SCM platforms that allows users to add files to other users’ repositories, often anonymously.

- They upload a malicious file to the targeted user’s repository.

- The attacker then reports the targeted user to the platform’s abuse team, claiming the account contains malicious content.

- In response to the report, the SCM platform deletes the targeted user’s account or repository.

If you want to see how this attack works, you can check out this 20 minute YouTube video.

It walks you through the disclosure presentation I delivered in Melbourne BSides in November 2024.

What is “swatting”?

Physical or “real-world” swatting is a terrible practice where a criminal makes a false report to emergency services to trigger an armed police response to an unsuspecting victim. The bad guy intends to get the police to go to the target’s house where often innocent people are hurt. Swatting became popular on 4chan and has now moved into the mainstream and is often abused by online gamers against other gamers.

This is a simple way to think of physical swatting:

Fundamentally, when someone swats another person they are abusing a system that is meant to do good (911) and twists it to do something evil. This abuse of a trust and safety mechanism is the important factor in this new “repo swatting” attack type.

Unfortunately, swatting in the physical world has led to real fatalities and real prison sentences.

Why are you talking about swatting?

As I mentioned above, physical swatting abuses the emergency services function to do bad things. This idea of abusing trust and safety mechanisms is something I saw bad guys doing in the software development lifecycle (SDLC) by abusing functions in GitHub and GitLab.

I wanted to understand this attack type more.

SCM platforms enable collaboration

I think it is important for everyone reading this to understand why SCM platforms like GitHub and GitLab are so powerful. I will discuss several features of these platforms and why they are targeted by criminals.

The primary value that SCM provides is not storing source code as much as it is the collaboration that happens *around* that source code.

- Companies store their source code in a SCM platform and developers use work emails to interact with source

- Startups and smaller orgs might let their developers use their own GitHub accounts with their personal email addresses

- Collaboration is the real business value to SCM platforms. They allow your software engineers and support staff to build and deploy applications

- Multiple developers working on the same project can check in code and the SCM platform manages how it’s integrated together (CI) and then deployed (CD).

- All of this involves LOTS of collaboration.

What explicit permission do you need to collaborate?

There are several ways you can collaborate with other users and their content on GitHub that require explicit permissions:

EDIT SOURCE IN WEB UI -You can edit source code directly in the GitHub or GitLab web UI. This requires that the original author gives you permission to edit the content. It’s not a common use case, but it’s supported. So, for example, I could add another user to my source code repository and say they are an editor, and they could change my repository any way they want. Again, this requires explicit permission.

FORKING – You can use a function in the SCM providers called “forking”. Forking creates an exact copy of someone’s repository in your account. So for example, if the original repo address was github.com/bob/test-app your copy would be github.com/your-user/test-app. Users can maintain their own fork of the original project, or more commonly they can use forking as a way to contribute code back into the original repository. This happens via a “merge request” or “pull request”. The original repository owner can look at the changes suggested by the fork owner and decide to merge those changes into the original. Then the fork is no longer necessary as its changes have been merged into main, and the fork can be deleted. Forking requires explicit permission in the sense that the original repository owner has to allow the changes made by the editor into their version of the code. They give their permission and then GitHub will merge the two repos together.

Are there ways to collaborate without explicit permission?

Yes! As surprising as this may sound to people unfamiliar with SCM providers, you can indeed interact with other peoples content without them giving you permission, or even knowing about it!

There are at least two ways you can collaborate with other users source code on GitHub without being given explicit permission:

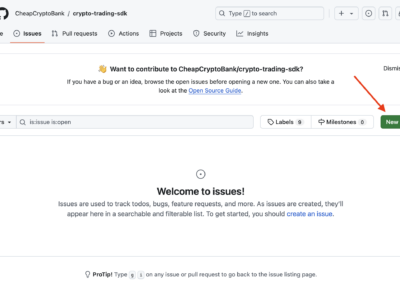

- GITHUB/GITLAB ISSUES – Any authorized user can go to another users project and create whats called an “Issue”. This is similar to creating a support ticket in other platforms. The idea behind Issues is that if you come across a problem, or an inconsistency, or anything else that you want to let the maintainer about, you can.

Sometimes GitHub Issues will be disabled or you can’t use that feature for some reason. There is another way to collaborate on someone else’s project without explicit permission:

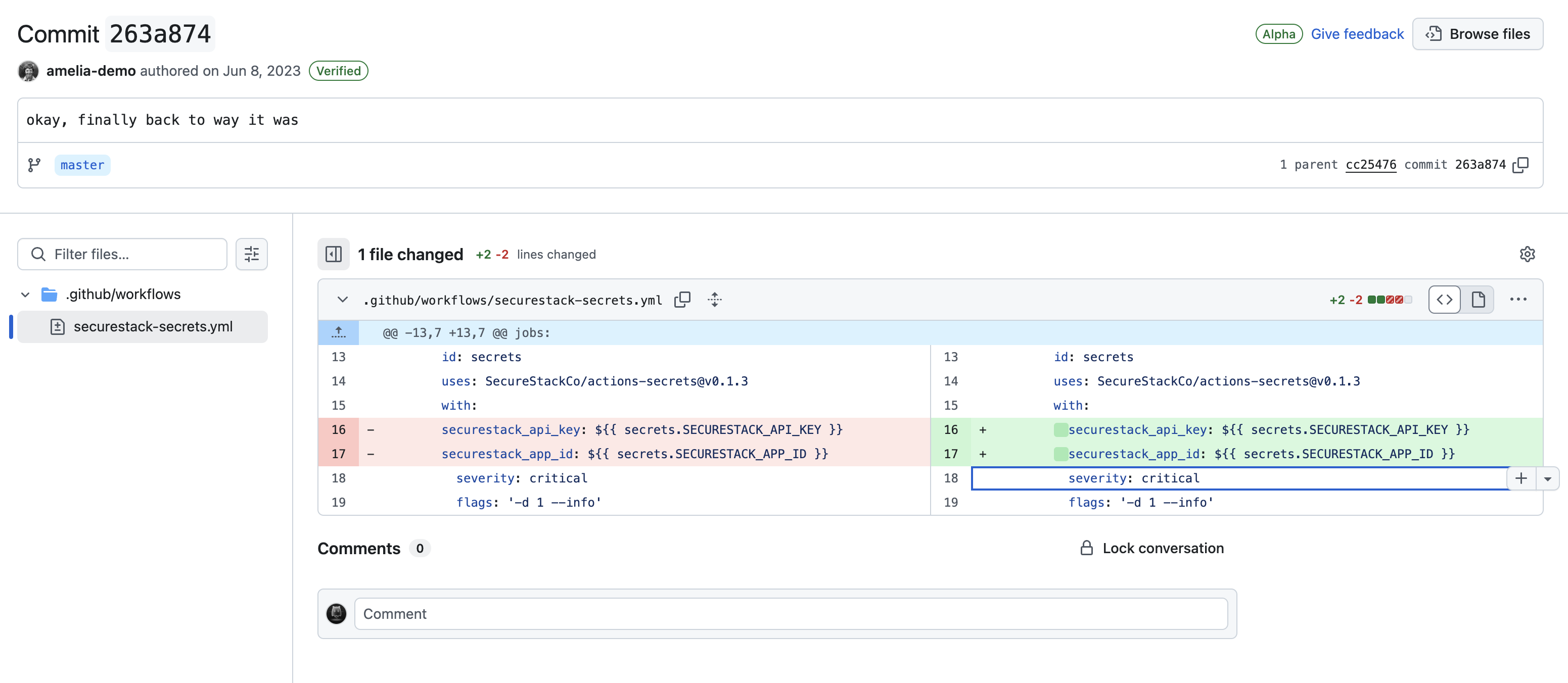

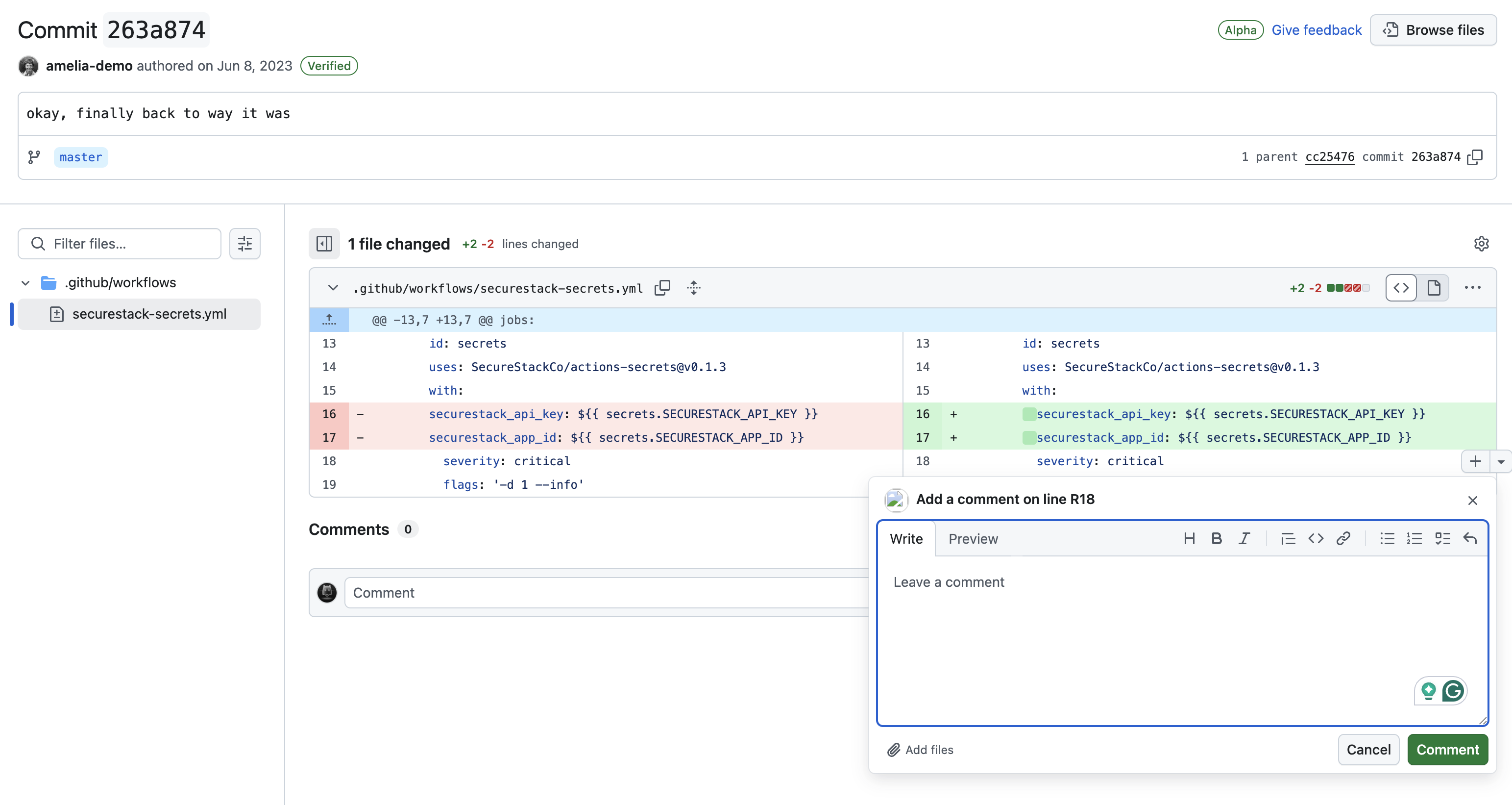

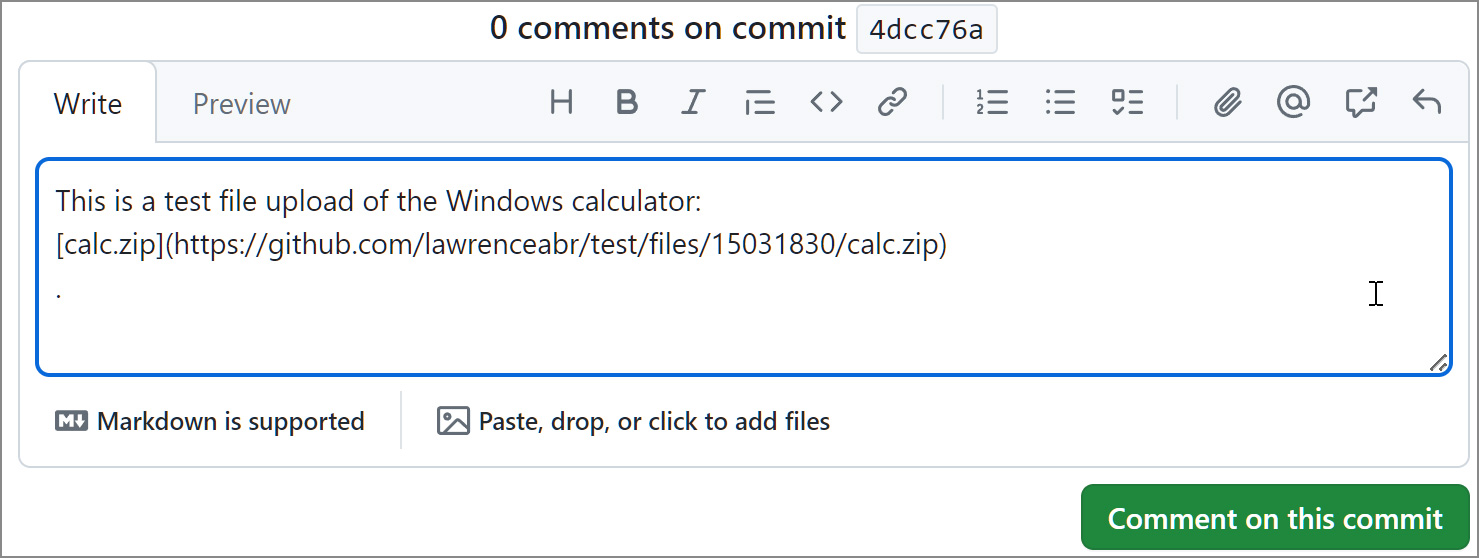

2. COMMIT COMMENTS – Any authenticated user can add comments to commits in the commit history. You simply browse to a git commit and click inside either of the two code comparison windows and a little plus will appear. If you click on that plus you’ll get a comment form much like the one in GitHub Issues.

This is where it starts to get crazy!

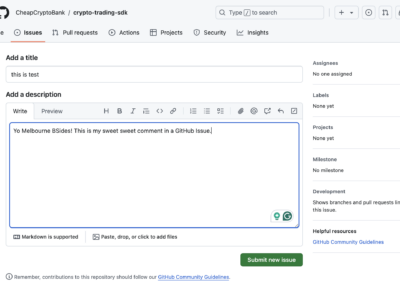

I think it makes a lot of sense for developers to make comments on other people’s work and to create “Issues” when they come across something that isn’t working right, or needs a tweak or whatever. But I think many people would be surprised to know that GitHub and GitLab allow people to add ANY type of file to the Issues and comments forms. You can drop image files like PNGs and JPGs. You can add video files like MP4 and MOV. You can add JSON blobs. You can even add executables and binaries!

Yes, you heard that right: GitHub and GitLab allow you to attach executable files to other people’s repos. In fact, until recently, GitHub allowed you to do this without even logging in to GitHub! You could just roll up to a GitHub repo, not have a GitHub account and drop files right into another users repository with no issues!

This is what the GitHub file upload looked like back in April 2024:

Source: BleepingComputer

It makes more sense if you watch the file upload as a video, so I’ve included one here. Notice that as soon as you drop the file into the form it immediately uploads the file.

Behind the scenes GitHub is uploading the files to the GitHub Objects UserContent CDN.

The GitHub UserContent CDN

To make the user experience better and faster, GitHub has created a CDN to host user content. This CDN hosts content in multiple locations around the world and is optimized for caching and speedy delivery. If you notice in the video above, as soon as you drop a file into the comment field it is immediately uploaded without the user having to do anything. The GitHub CDN is very greedy and will take anything you give it and upload it. GitLab has done the same thing and their CDN works almost exactly the same way.

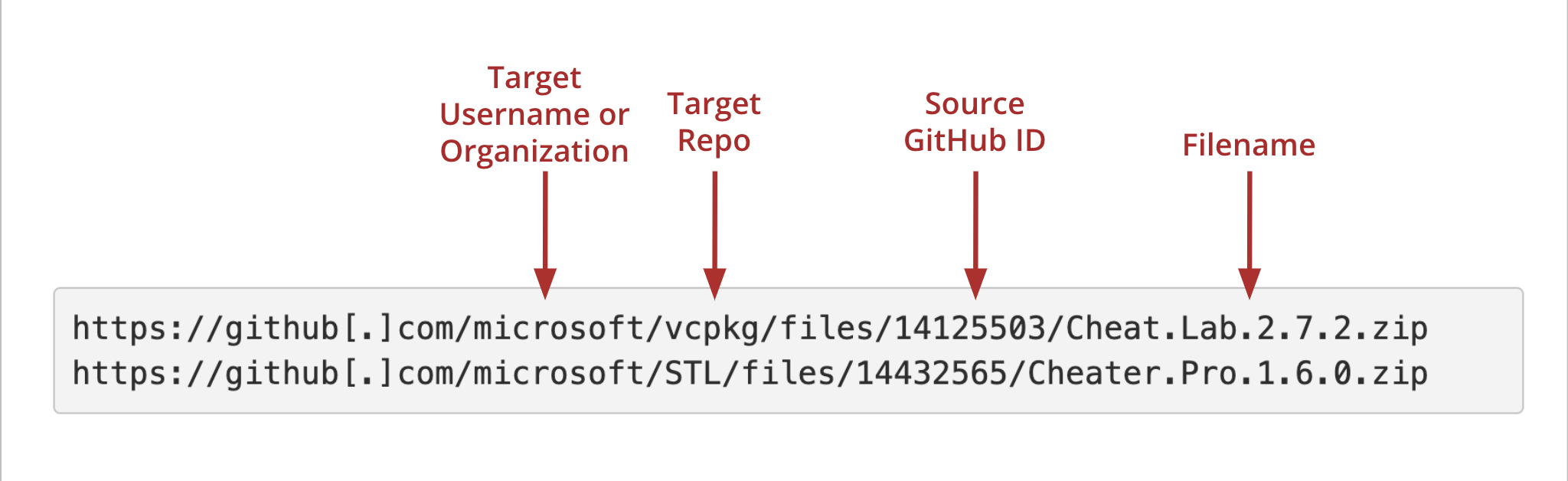

Let’s see how GitHub is naming the files once they are uploaded to their CDN:

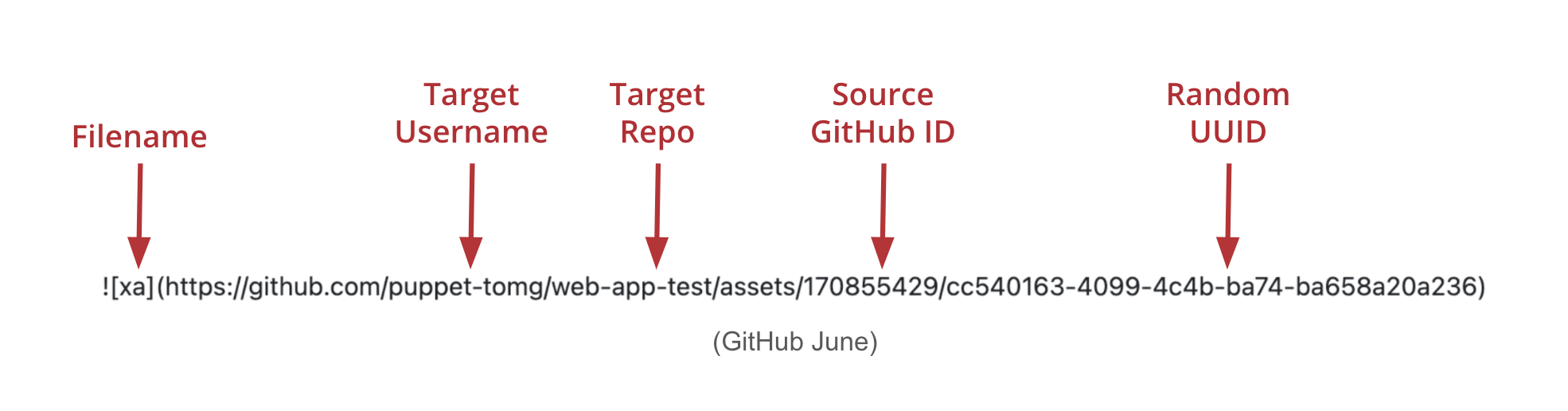

The URL path that GitHub was creating on the fly back in April 2024 included the target users account, target repo, the source GitHub ID of the person who uploaded the file, and finally the file name.

Once that file was uploaded to the CDN it was immediately available there and anyone in the world could go to that URL and download the file. On the backend GitHub’s CDN leverages Amazon’s S3 service to store all the user content. This is mildly amusing to me considering that Microsoft owns GitHub and has its own blob storage service, but uses AWS instead.

GitHub’s CDN abuse escalates

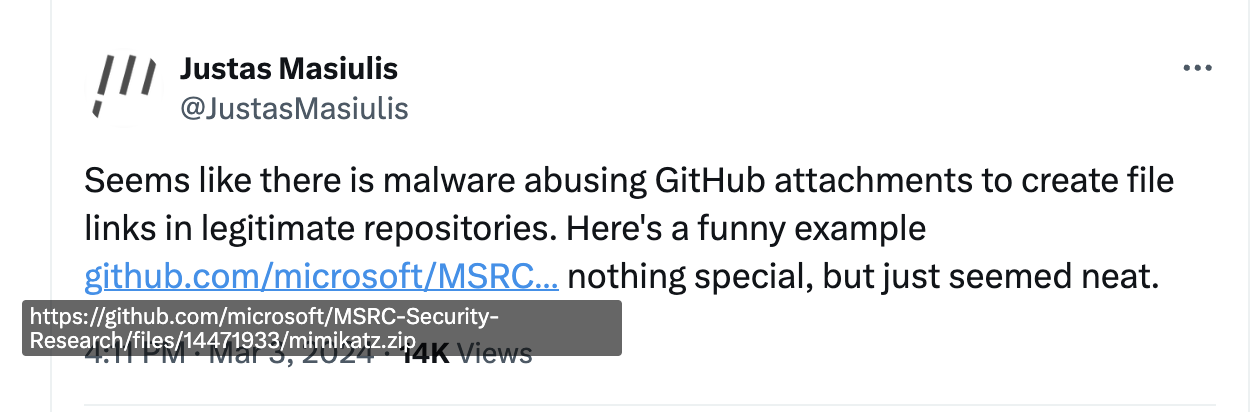

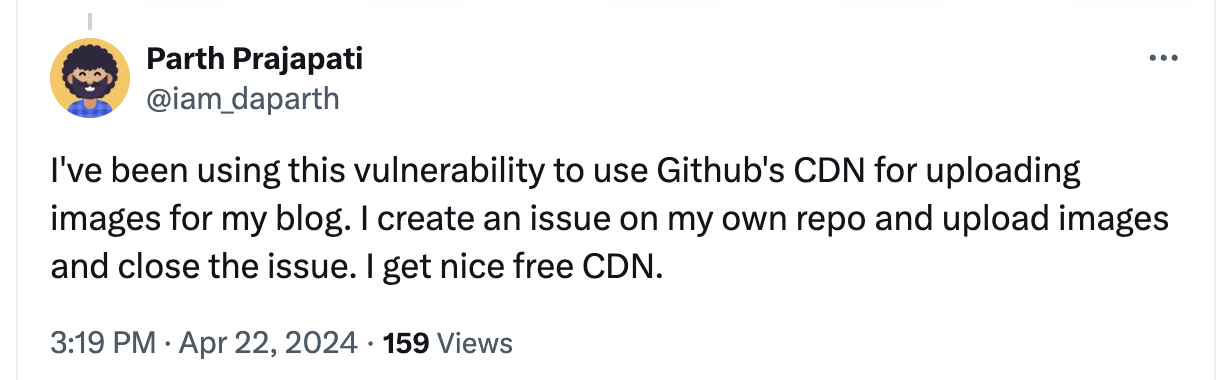

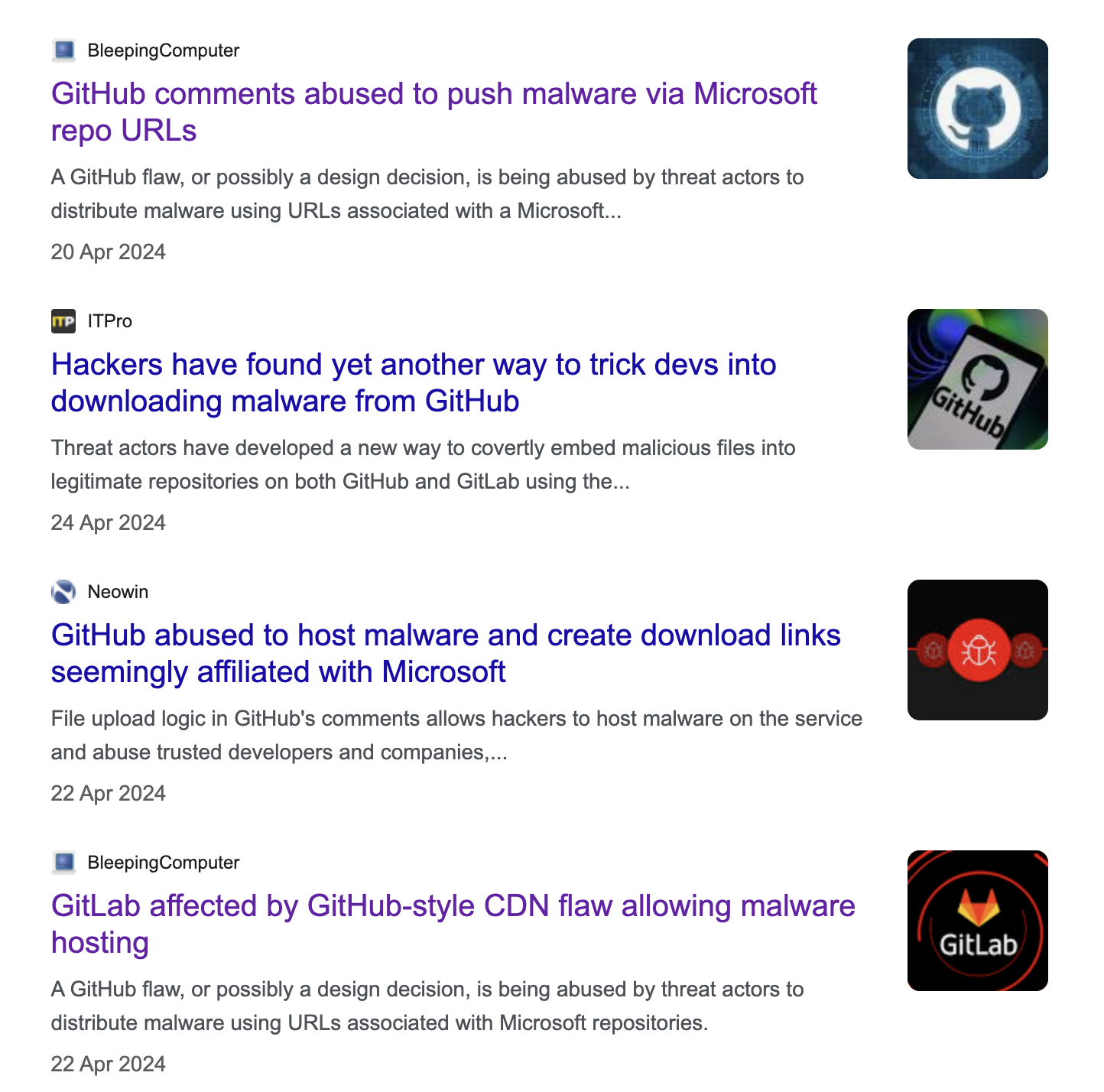

In April 2024 several media outlets started picking up on the file upload “feature” and how people are abusing it.

Very quickly people realize that GitLab has the exact same issue. The only real difference is that you had to be logged in with a viable GitLab user before you could upload files. GitHub on the other hand did not require that you had an account.

At first, the abuse was funny, and not diabolical in any way. Someone for example uploaded mimikatz to a Microsoft repo. I mean, that’s pretty funny, right?

But wait, it got worse, really quickly!

It turned out that the file upload “vulnerability” was even worse than originally thought as you didn’t need to finish or submit the GitHub Issue or comment that the file was in. If you just waited for it to upload you could then cancel, or back out of the Issue and the file would still be accessible, but there would be no evidence of the Issue or comment.

This is when the floodgates really opened and bad guys started using the file upload feature in earnest.

Every media outlet with a tech desk ran a story. It was crazy!

My moment of epiphany

I was watching this really funny video when I got a bright idea. Security researcher @herrcore was doing a live demo of the GitHub file upload bug when one of the people on his stream dropped mimikatz into his GitHub repo. You can see the moment I’m talking about at 2:18 in the video.

I laughed out loud but then I had a thought… I wonder if I can combine this file upload bug with an abuse complaint in GitHub?

Weeks later... GitHub bug still dropping malware 👌 pic.twitter.com/s165zOAsoI

— herrcore (@herrcore) March 27, 2024

Could I get a repo flagged, or taken offline?

Or worse?!

Let’s test my theory…

So, my theory was that I could combine the GitHub anonymous file upload feature with an abuse complaint and maybe get a repo taken offline.

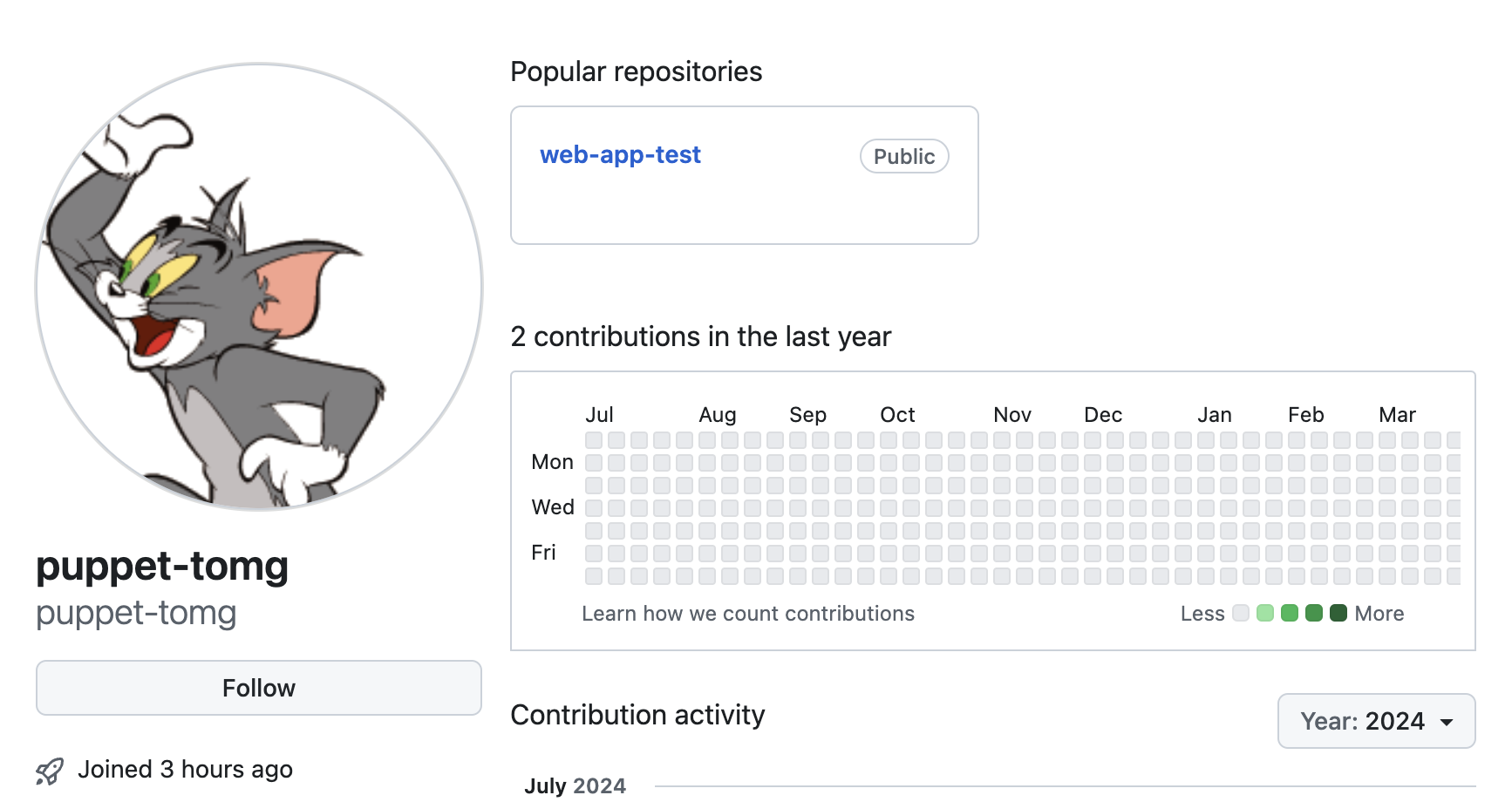

I needed to test this so I spun up a “code puppet”. A code puppet is a sock puppet for GitHub and GitLab. If you aren’t familiar with sock puppets you can think of them as disposable personas you use while doing security research. Why? Because, you don’t want to do this stuff as yourself, right?

BTW, I have a whole section about creating and identifying code puppets in my training. My students love it and its typically their favorite part of my training!

Ground rules for testing

No innocent bystanders were hurt during the testing of this vulnerability. In other words, all accounts involved were my own code puppets. I asked a couple of my friends if I could try and repo swat them, but they weren’t interested in being guinea pigs.

I originally started researching this attack back in February 2024. Over time all the SCM providers mentioned in this article have made important changes to their platforms to address these attack vectors. I think it’s important to note that the number of attacks, and the sheer volume of malicious content being created in these platforms is increasing. Both GitHub and GitLab have great teams working on these problems, and this blog post should not be seen as disrespecting their work and the changes they’ve introduced to their respective platforms.

Okay, let’s get this ball rolling…

The target

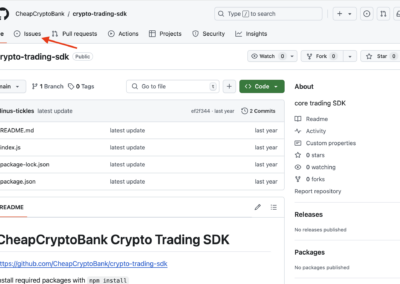

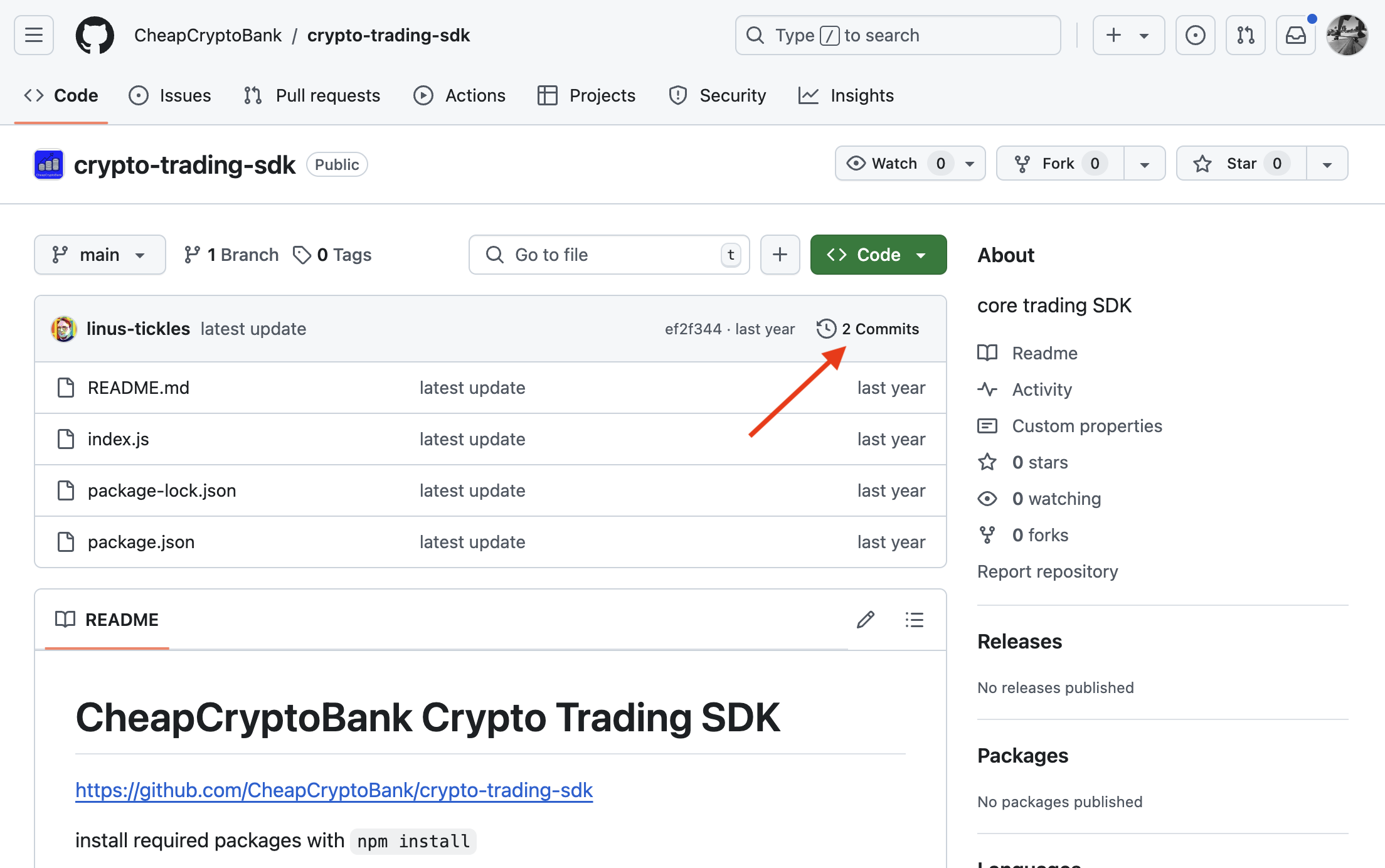

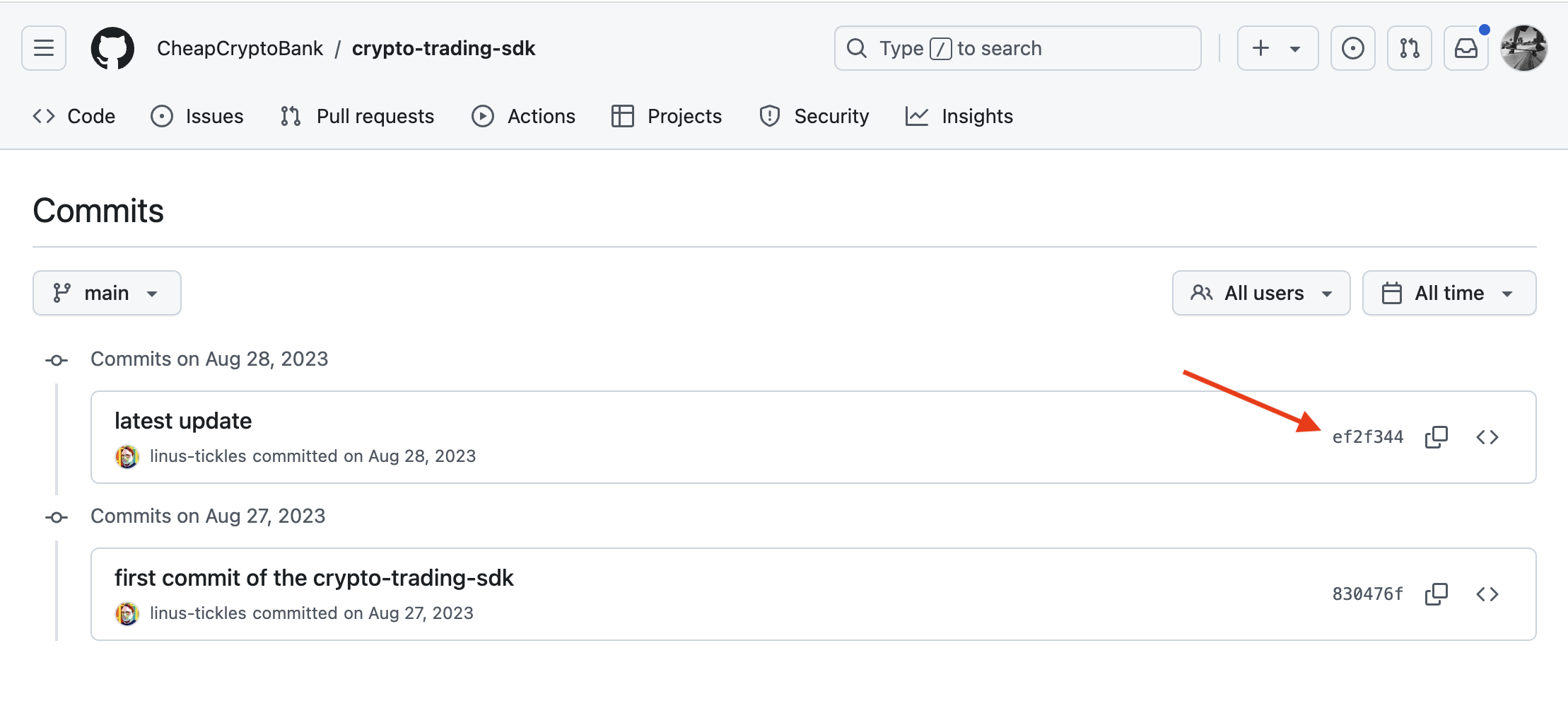

So, I started with a brand new code puppet named puppet-tomg. I then create a quick repository with a simple web app in it.

Upload the malicious files

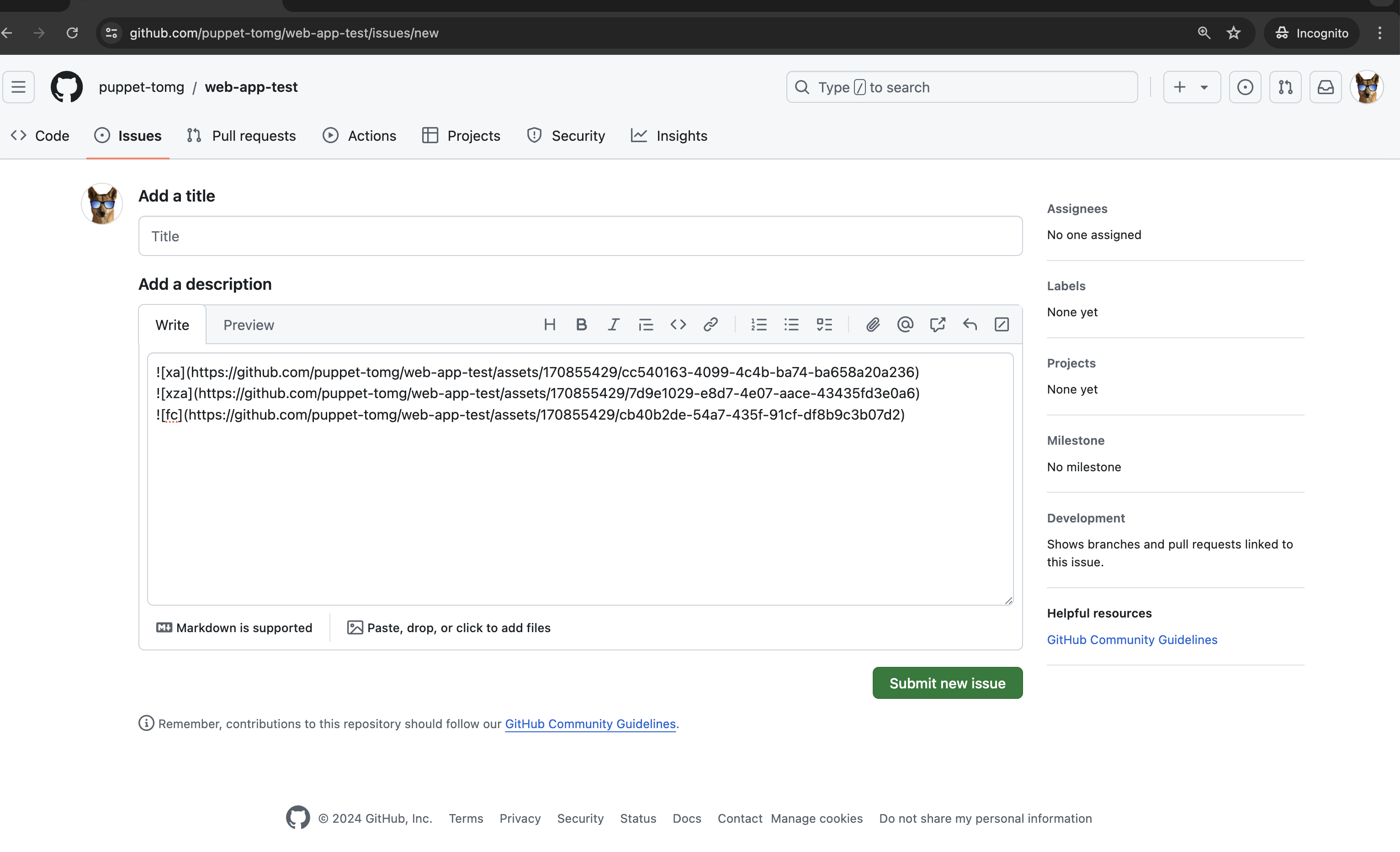

Next, I used another code puppet to attach 3 different crypto miners to puppet-tomg’s web-app-test repo.

Submit abuse form

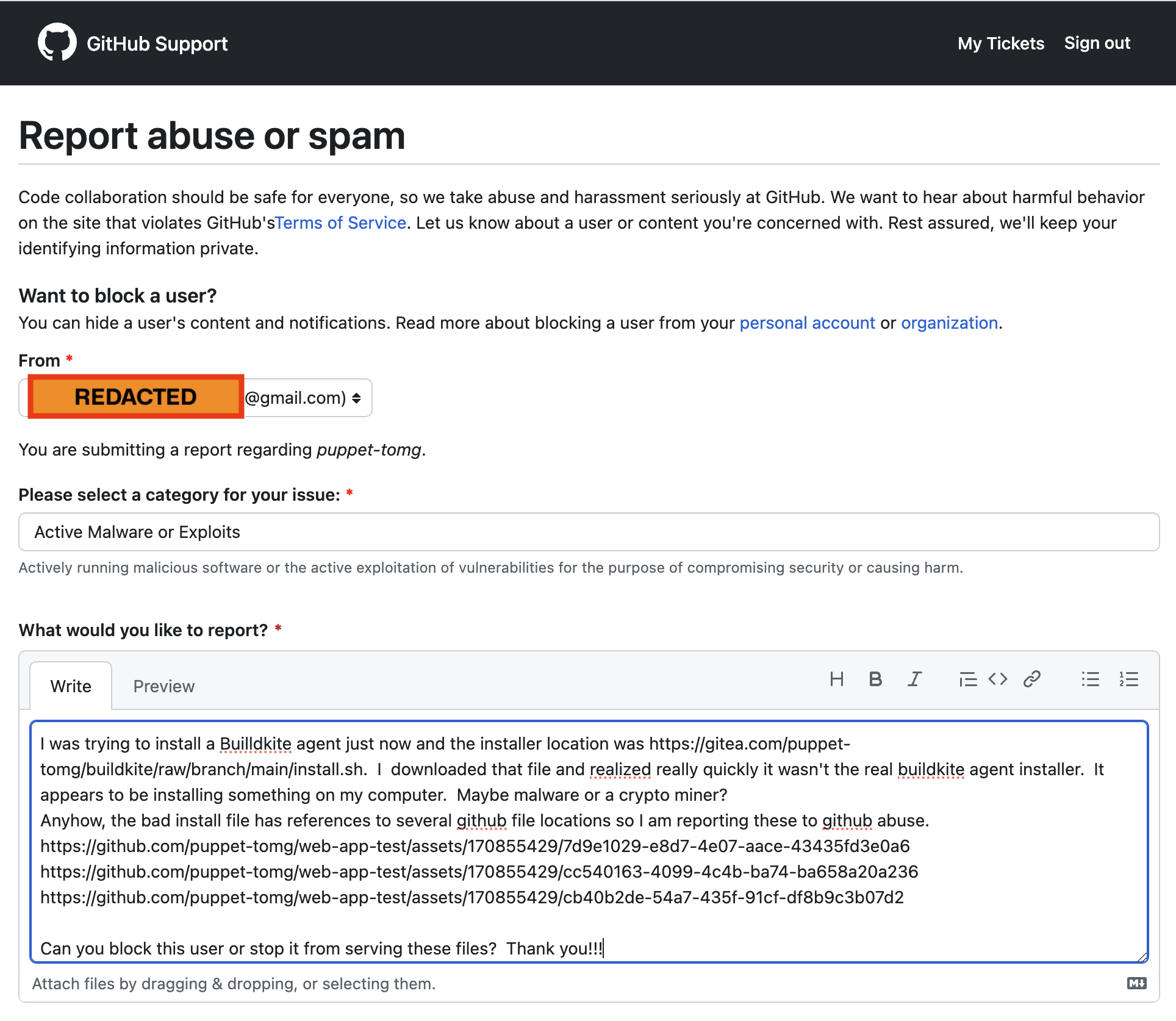

The last step was to report the account via the GitHub abuse function. In this case I made up a whole story that the account was serving malware.

Wait for GitHub to respond

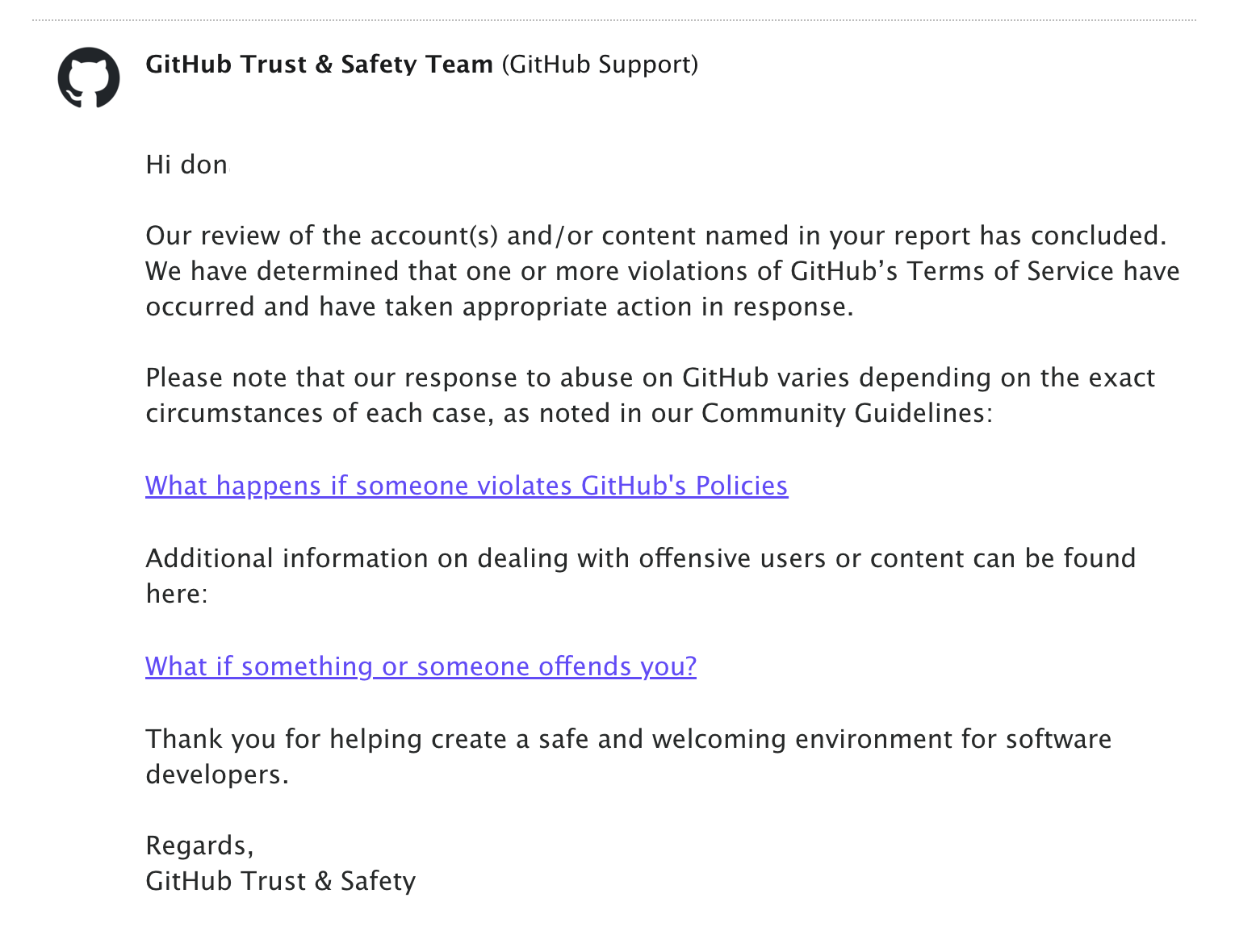

After I submitted the abuse form I got an auto-generated email thanking me for submitting the abuse form. Then I waited.

Then a few weeks later I got this email. It said in part “We have determined that one or more violations of GitHub’s Terms of Service have occurred and have taken appropriate action in response.”

But what did this mean? I checked my code puppets email and had no emails from GitHub.

Had GitHub done anything at all?

The penny drops

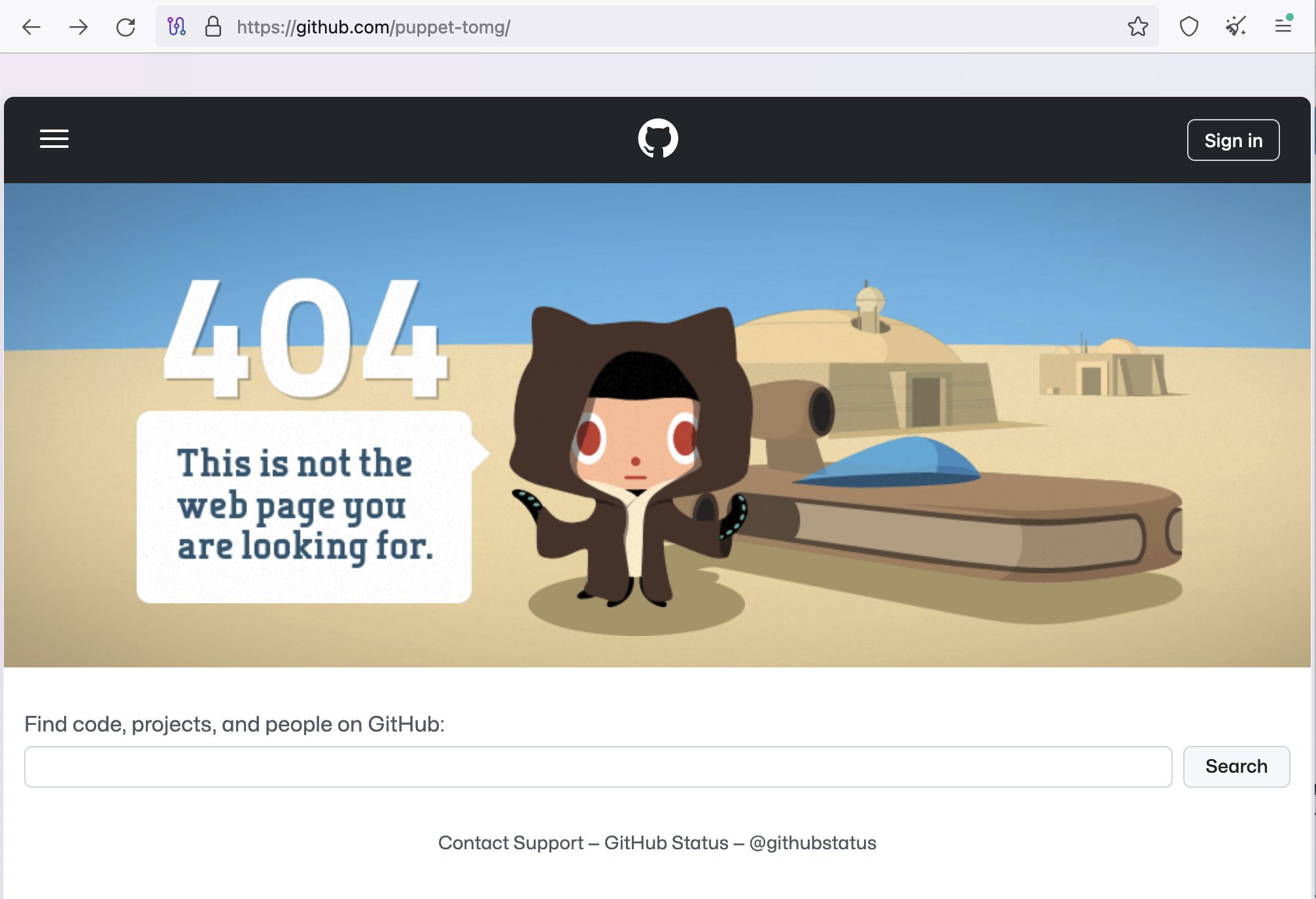

I went to GitHub to check on the puppet-tomg account and I got an error. I refreshed and then realized what had happened: The account had been deleted.

It had worked. I was in shock! Sure, it had taken several weeks, but it was successful. I now had proof that repo swatting could successfully delete a GitHub account.

Repo Swatting Playbook

So we are all on the same page here, let’s go over how this attack works:

- An attacker exploits a “feature” in SCM platforms that allows users to add files to other users’ repositories, often anonymously.

- They upload a malicious file to the targeted user’s repository.

- The attacker then reports the targeted user to the platform’s abuse team, claiming the account contains malicious content.

- In response to the report, the SCM platform deletes the targeted user’s account or repository.

It’s an incredibly simple attack vector, and frankly when I originally theorized that I might be able to do it, I didn’t think it would be that easy. But it is.

Can I do this in GitLab too?

I wanted to see if I could successfully repo-swat an account in GitLab. A few things in GitLab were different but overall the platforms handle file upload and abuse reports in very similar way.

This video shows an end-to-end repo swat in GitLab. Overall, the response time in GitLab was much faster than GitHub.

Chronology of events and mitigations

Since I’ve been researching this attack, both GitLab and GitHub have made various changes to their platforms to address repo-swatting. In particular, the URL pathing that the platforms are now using and changes on their backend have made repo swatting very difficult or impossible. I have not been able to repo swat successfully since the latest changes were made in October 2024.

April 2024 – Mainstream media picks up on the fact that GitHub is being used to host malware (and other bad things)

April 2024 – GitHub’s file upload URL path looks like this:

May 2024 – GitHub’s first attempt at mitigating repo-swatting changes the URL path for uploaded items to use https://github.com/<target user>/<target repo>/assets/<UUID> instead of https://github.com/<target repo>/<target user>/files/<filename>

May 2024 – GitHub requires that all file uploads now have an extension. This doesn’t do much as a mitigation as you can still host any file type you want, it just has to have a file extension.

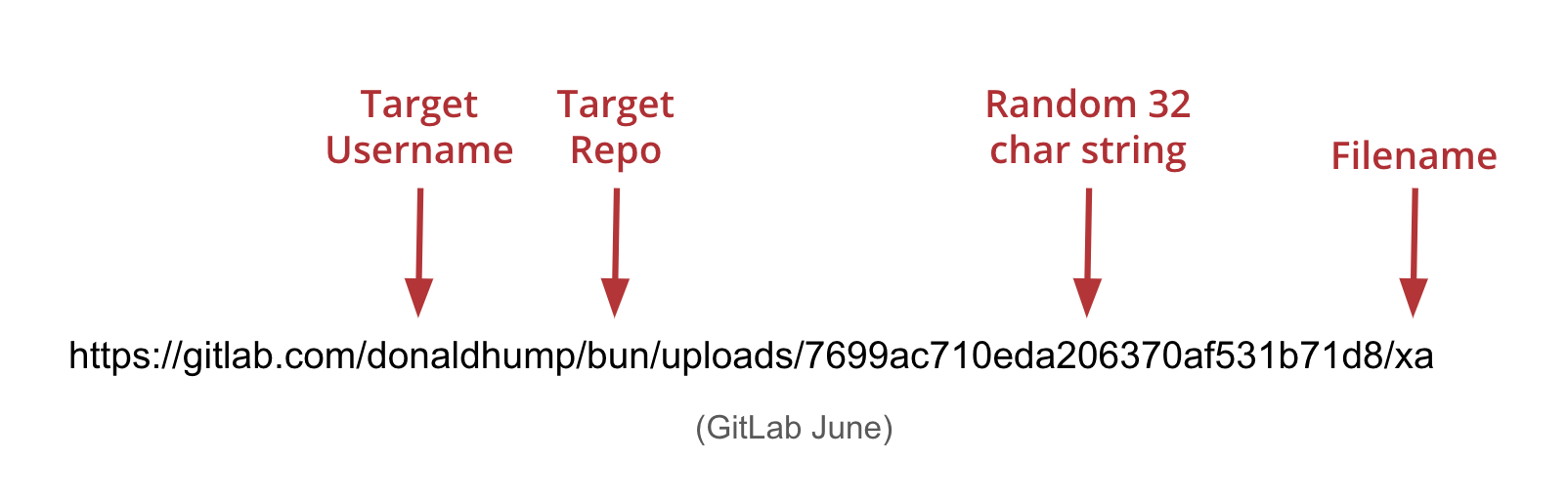

June 2024 – GitLab’s file upload URL path is https://gitlab.com/<target user>/<target repo>/uploads/<UUID>/<filename>

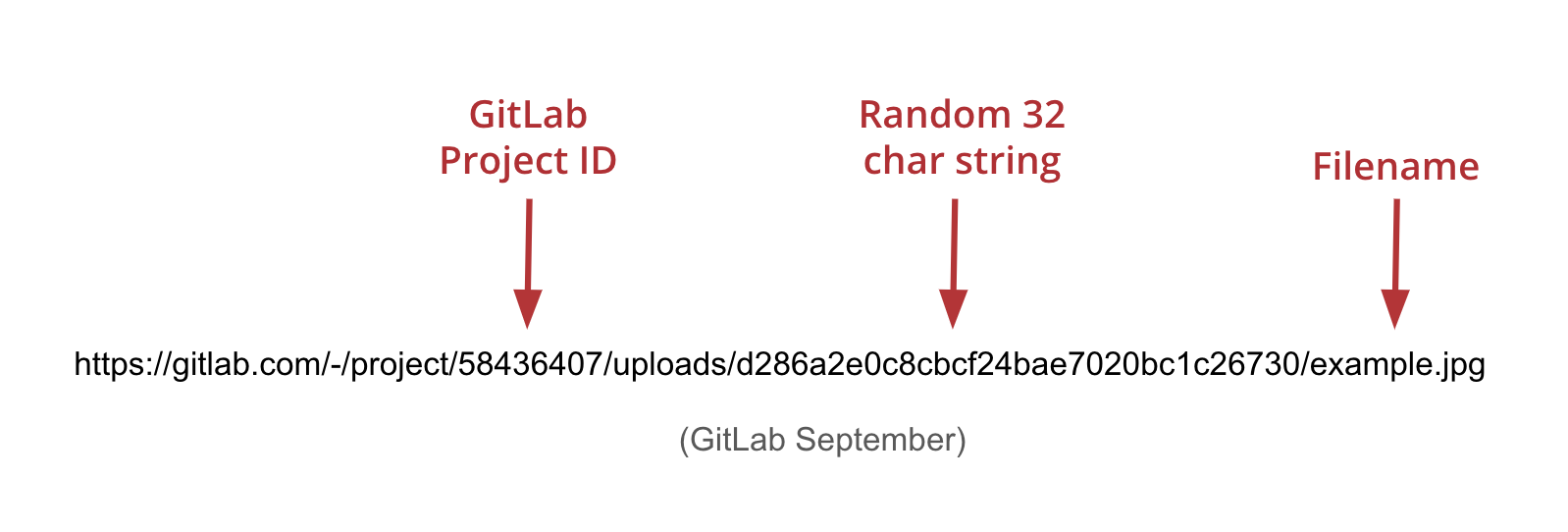

September 2024 – GitLab changes the file upload URL path to be https://gitlab.com/~/project/<project id>/uploads/<UUID>/<filename>

October 2024 – GitHub changes the URL path again to https://github.com/user-attachments/assets/<UUID>. This effectively kills repo swatting as the connection between the target and file is now broken.

October 2024 – GitHub requires that you authenticate as a GitHub user to upload files to GitHub. No more anonymous uploads!

Actually, GitHub weakens their new account onboarding so you can make a fake account (“code puppet”) in less than a minute with Proton account. Hello anonymous uploads!

Has the repo swatting attack been mitigated?

The short answer is “mostly”, but the longer, more honest answer is “I don’t know”. The changes that GitLab made in September and that GitHub made in October seem to have addressed the “tight coupling” between a malicious file upload and a target user account that made repo swatting work so well. However, you can still upload malicious files to other people’s repositories so will people find other attacks that leverage this file upload function? Maybe. Probably even.

Where do we go from here?

File uploads are an integral part of SCM platforms but this feature also carries a lot of risk, especially when the platform allows you to attach files to someone else’s account. As such this is not an easy problem to solve, because as the joke goes “it’s a feature, not a bug”.

I suspect that eventually, the SCM platforms will limit file uploads to files with image extensions like .png, and .jpg. However, this doesn’t stop a bad guy from uploading a crypto miner binary and naming it “payload.jpg”.

This is also a hard problem to solve with automation and that means that the SCM providers will need lots of people involved in this content safety work. This problem is made worse by the fact that the actual uploading of files to these platforms (ie., the abuse) can be automated, but the ability to find these needles in the haystack cannot be effectively automated. This disparity in automation effectiveness means the humans will always be outgunned.

What makes repo swatting so powerful

- Anonymity: On some platforms, like GitHub and Gitea, files can be attached to repositories without logging in, making the attack truly anonymous.

- Ease of Execution: Even on platforms requiring an account, it’s simple to create new, anonymous accounts for this purpose.

- Potential for Abuse: This attack could be weaponized to take developer resources offline, potentially causing significant disruption to individuals or organizations.

- Difficulty in Mitigation: As SCM providers consider this a “feature,” it’s challenging to prevent without significant changes to platform functionality.

Thanks for reading this long blog post. If you have any questions, feel free to reach out.